Vatican

The Vatican

‘To renovate the very dilapidated church of St. Peter the Apostle in Rome from its foundations up and to provide it in seemly fashion with chapels and other necessary rooms.’

Letter of Pope Julius II to King Henry VIII and the Lords Spiritual and Temporal of England, January 1506.

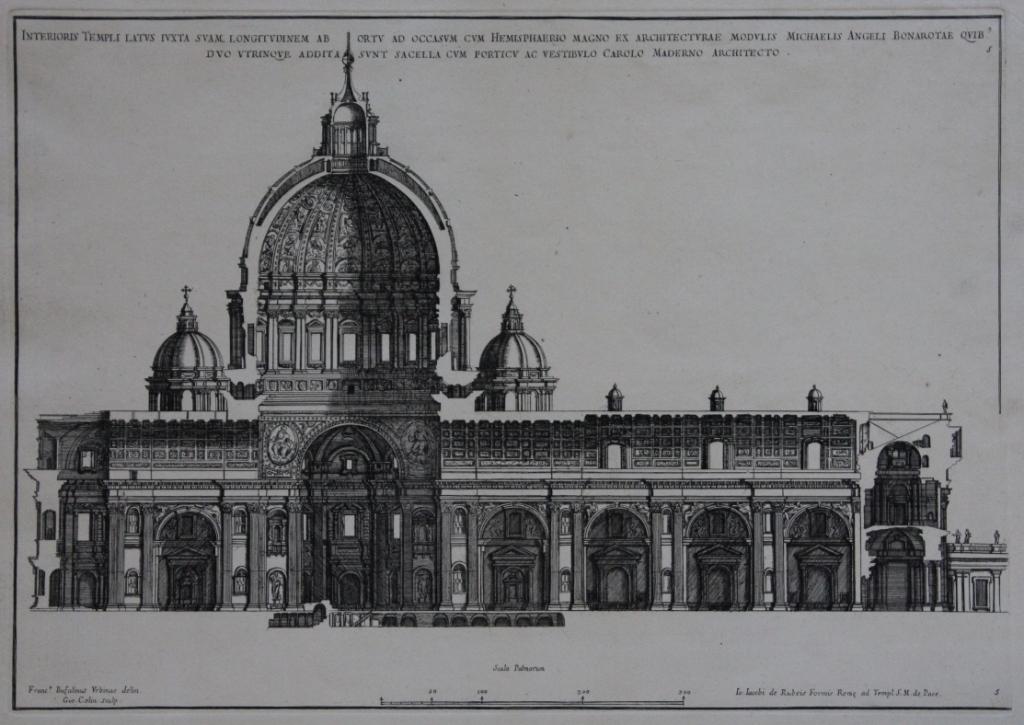

Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi, Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684), plate 3 (front elevation of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican).

The Basilica of St. Peter’s at the Vatican is one of the most iconic buildings, not only of Rome, but of the world. Its role within the Roman Catholic Church as the seat of the papacy, coupled with the ability of the papacy to build on a monumental scale, has ensured that over the centuries the basilica has evolved from a relatively simple church to the grand basilica which we know today. Worth owned a number of books which focused on the various plans for St. Peter’s, but undoubtedly his most important was Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi’s Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684). This was a deluxe collection of engravings of churches in Rome, which naturally paid particular attention to St. Peter’s Basilica.

De Rossi (1627-1691) was an accomplished engraver and printer in seventeenth-century Rome. The fact that his father, Giuseppe de Rossi (1570-1639) had founded one of the most active printing presses in seventeenth-century Rome (a press in which Giovanni Giacomo and his brothers played an important role), was of undoubted benefit to Giovanni Giacomo as it enabled him to master all elements of the print trade. The result is his beautifully produced Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque which included engravings not only by de Rossi himself, but also by engravers such as Francesco Bufalini, Lorenzo Nuvolone, Giovanni Francesco Venturini and Jean Collin. As Pollak (2000) comments, De Rossi had been particularly active between 1647 and 1691 in creating engravings himself but, in addition, commissioning engravings from other artists. Using this work, and Worth’s copy of Filippo Buonanni’s Numismata summorum pontificum Templi Vaticani fabricam indicantia, chronologica ejusdem fabricae narratione, ac multiplici eruditione explicate (Rome, 1696), we can piece together the architectural history of the Vatican and St. Peter’s Basilica.

Filippo Buonanni, Numismata summorum pontificum Templi Vaticani fabricam indicantia, chronologica ejusdem fabricae narratione, ac multiplici eruditione explicata (Rome, 1696), plate 5 (old basilica of St. Peter’s).

This plate, from Buonanni’s Numismata summorum pontificum Templi Vaticani depicts the fourth-century Basilica of Constantine (c.272-337). Buonanni had already plotted the relationship between the old Circus of Nero, the old Basilica of St. Peter’s and the plans for a new basilica (his plate may be seen on the Rome webpage). As the above plate shows, the basilica built by the Emperor Constantine between 319 and 333 AD, had the typical basilica shape: i.e. a very wide nave with an aisle on each side and an apsidal end. This building, built over the remains of St. Peter himself, lasted many centuries but by the end of the Middle Ages was beginning to deteriorate. The popes of the later fifteenth and early sixteenth-century knew that the church needed to be rebuilt. They were keen to do so in such a way that their building would reflect the prestige of the papacy throughout the world. Unlike the relatively simple Basilica of Constantine, the new basilica would be a far grander structure, one which would proclaim papal power to the world.

The key figure in this rebirth of St. Peter’s Basilica, and more generally the Vatican itself was Pope Julius II (1443-1513). True, Pope Nicholas V (1397-1455) had laid foundations for a basilica in the shape of a Latin cross, but beyond that little had been achieved. Julius II, from his elevation to the papacy in 1503, was far more active and the next ten years laid the groundwork for what we see today. Having already commissioned Michelangelo (1475-1564) to design a monumental tomb for him, Julius decided, in 1505, to rebuild the Basilica of St. Peter’s on a grandiose scale. A competition was held and Donato Bramante (1444-1514) was chosen. His 1506 plan for the basilica was based on that of a Greek Cross, which would be capped by a dome, echoing the dome of the Pantheon. Julius II, in order to finance the rebuilding of the fabric of the church, issued a call for indulgences, a call which would lead to the fracturing of the spiritual body of the church.

Filippo Buonanni, Numismata summorum pontificum Templi Vaticani fabricam indicantia, chronologica ejusdem fabricae narratione, ac multiplici eruditione explicata (Rome, 1696), plate 16 (longitudinal section of Sangallo’s design for St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican).

By the time of Julius II’s death in 1513 little had actually been achieved: the old St. Peter’s was already partially demolished and the foundations for Bramante’s dome were beginning to show cracks. Despite this, as Lotz (1995) notes, the plan for a dome was retained. Julius II’s successor, Pope Leo X (1475-1521), employed Giuliano da Sangallo (c.1445-1516) and Fra Giocondo (c.1433-1515) to remedy the situation (a situation made all the more difficult by Bramante’s death in 1514). These in turn were superseded shortly after Bramante’s death, when Leo X appointed Raphael as architect-in-chief of St. Peter’s on 1 August 1514. Raphael was given an assistant, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger (1485-1546), a nephew of Giuliano’s – who would work as coadjutor (in effect, as Lotz says, planning and executing the finished drawings). On Raphael’s death in 1520, da Sangallo the Younger became architect in chief and remained so until his death in 1546.

The above plate shows a longitudinal section of da Sangallo the Younger’s plan. It was, as we can see, an ambitious one, but was subject to the political vicissitudes of the time: the Sack of Rome in 1527 ensured that building on St. Peter’s was moved down the list of papal priorities and between 1527 and 1540 little work was done. A renewed attempt to increase finance was made by Pope Paul III (1468-1549), who became pope in 1534. Incan gold, flooding into Spain and from thence to papal coffers, enabled a model of da Sangallo the Younger’s plan to be built and the floor to be raised. We can see here that da Sangallo the Younger retained the central structure of Bramante with its dome and four corner towers, but to this he added a huge eastern façade with two large towers. As Lotz (1995) remarks, ‘in view of the lack of funds the project remained utopian.’

Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi, Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684), plate 5 (longitudinal section of Michelangelo‘s design for St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican).

We can compare Buonanni’s plate of da Sangallo the Younger’s longitudinal section with a similar section of Michelangelo’s design for St. Peter’s Basilica from de Rossi. As Pollak (2000) explains, de Rossi favoured depicting churches in his Insignium Romae templorum in orthogonal architectural representation (plan, section, and elevation). In this he was following a pattern laid down by Raphael. It was a pattern which eminently suited de Rossi’s project of teaching architecture by example. As Pollak (2000) notes, this approach was new, breaking away from older treatises which focused on rules and principles. This section view shows that Michelangelo dispensed with da Sangallo the Younger’s utopian towers.

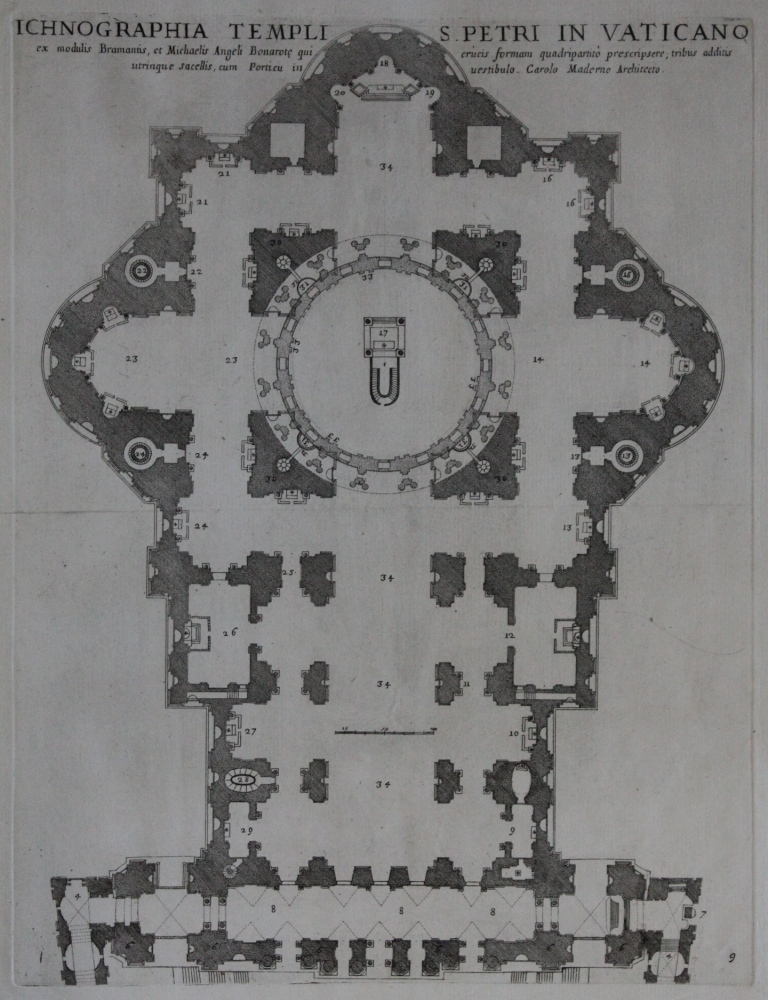

Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi, Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684), plate 9 (Michelangelo’s plan of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican).

Michelangelo succeeded da Sangallo the Younger as architect-in-chief of St. Peter’s on the latter’s death in 1546. By the time of his own death in 1564 great progress had been made: much of the transept (i.e. the north and south arms) was completed, as was the drum of the dome. As Lotz (1995) notes, the chancel (the west arm) would be finished in the later sixteenth century to Michelangelo’s plan. Lotz (1995) draws attention to the fact that Michelangelo placed more emphasis on strengthening the outer walls: their articulation was now identical with the walls bounding the inner structure and harked back to Bramante’s plan in spirit, if not in the letter of the law.

Filippo Buonanni, Numismata summorum pontificum Templi Vaticani fabricam indicantia, chronologica ejusdem fabricae narratione, ac multiplici eruditione explicata (Rome, 1696), plate 25 (section of dome of St. Peter’s Basilica, Vatican).

A model, dating to the period 1558-1561 survives of Michelangelo’s plan for the dome of St. Peter’s, which would later be completed by Giacomo della Porta (c.1533-1602) in the later 1580s. Both were double-shelled structures, though the dome erected by della Porta between 1588 and 1591 was more pointed than that of Michelangelo’s model. The hemispherical form of Michelangelo’s dome was intentionally reminiscent of Bramante’s plan, and, via it, of the celebrated dome of the Pantheon, but Michelangelo also had in mind Brunelleschi’s dome of Santa Maria del Fiori (the Cathedral of Florence, his home town).

Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi, Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684), plate 10 (plan of St. Peter’s Square, Vatican).

Though Michelangelo’s plan for the Basilica of St. Peter’s remained dominant, two other architects played a vital role in the development of St. Peter’s in the seventeenth century: Carlo Maderno (1556-1629) and Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680). We have already seen a plate of Maderno’s Baroque façade of St. Peter’s at the top of this webpage. This façade was completed in 1612 and the date was memorialised in an inscription below the cornice: IN HONOREM PRINCIPIS APOST PAVLVS V BVRGHESIVS ROMANVS PONT MAX AN MDCXII PONT VII (In honour of the Prince of Apostles, Paul V Borghese, a Roman, Supreme Pontiff, in the year 1612, the seventh of his pontificate). Pope Paul V (1550-1621), on his election as pope in 1605, had appointed Maderno to not only design a façade for the basilica but also to increase the size of the nave – thus converting what had been a building in the shape of a Greek Cross to that of a Latin Cross. This plan, which substantially altered Michelangelo’s design, was completed in 1615.

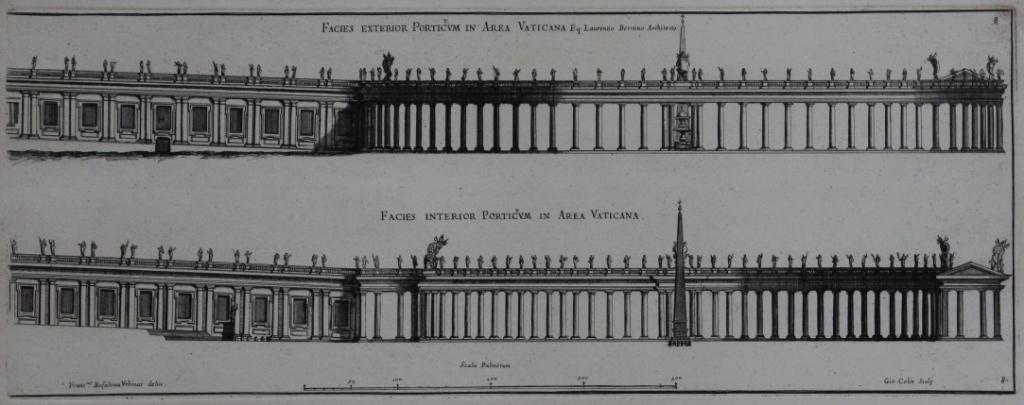

Maderno was succeeded as architect-in-chief by another famous Baroque architect, Gian Lorenzo Bernini, who was responsible for designing St. Peter’s Square, and, the epitome of Baroque style, the highly ornamental baldacchino over the high altar of St. Peter’s. Building work on St. Peter’s Square began in 1657 and, three years later, much of the north colonnade had been completed. As Metzger Habel (2013) points out, the construction of such a large piazza had massive implications not only for the area of the Vatican, but also for building projects around Rome: it concentrated papal finances on buildings closer to home and, at the same time, diverted skilled labour away from other building projects in the city. And there were other problems, for the new piazza had to incorporate the Egyptian obelisk known as the ‘Witness’ since it had been put in place on the Circus of Nero in 37 AD and therefore had witnessed the martyrdom of St. Peter. It was centrally placed in relation to Maderno’s façade and it was deemed too difficult to move. In addition, a fountain erected by Maderno posed other spacial problems for Bernini. The latter’s solution was to divide the piazza into two areas, a trapezoidal shape encompassing both the obelisk and the fountain; this connected with a large elliptical space outlined by double columns of the Tuscan order.

Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi, Insignium Romae templorum prospectus exteriores interioresque a celebrioribus architectis inveni nunc tandem suis cum plantis ac mensuris a Io. Iacobo de Rubeis Romano suis typis in lucem editi ad aedem pacis cum privilegio summi pontificis. Anno. 1684. (Rome, 1684), plate 8 (elevation of outer and inner colonnades of St. Peter’s Square, Vatican).

Sources

‘Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi’ entry in Pollak, Martha (ed.) The Mark J. Millard Architectural Collection. Volume IV : Italian and Spanish Books, Fifteenth to Nineteenth Centuries (Washington, 2000).

Hopkins, Andrew, Italian Architecture from Michelangelo to Borromini (London, 2002).

Lotz, Wolfgang, Architecture in Italy 1500-1600 revised by Deborah Howard (Yale University Press, 1995).

Metzger Habel, Dorothy, “When all of Rome was Under Construction” : The Building Process in Baroque Rome (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2013).

Millon, Henry A., The Triumph of the Baroque : Architecture in Europe 1600-1750 (London, 1999).

Text: Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library.